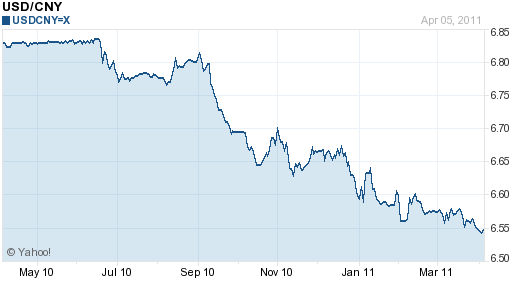

Since the People’s Bank of China (PBOC) unfixed the Chinese Yuan in June, it has appreciated 4.5%. Moreover, for a handful of reasons, it looks like China will continue allowing the RMB to appreciate at the same steady pace for the foreseeable future. And yet, the international community continue to use China as a scapegoat for all global economic ills, and are pressuring it to stop trying to control the Yuan altogether.

At the recent G20 conference in China, US Treasury Secretary Tim Geithner circumvented China’s request to avoid discussing its currency policy: “Flexible exchange rates help countries better absorb shocks and that the tension between flexible currencies and those that are ‘tightly managed’ is ‘the most important problem to solve in the international monetary system today.’ ” Naturally, Chinese officials countered that the Dollar is to blame for the recent financial crisis and the ongoing economic imbalances.

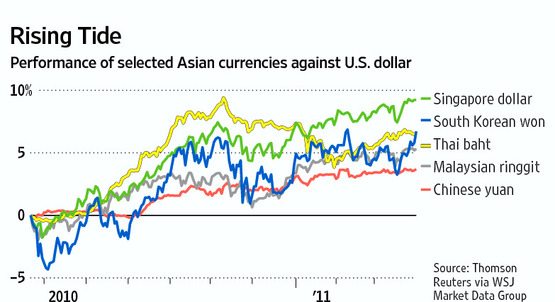

If China was the only country to attempt to control its currency, perhaps the rest of the world would be willing to overlook it and write it off to ideological differences like they do with many of its protectionist economic policies. In this case, however, China’s tight control of the Yuan has spurred many of the countries with which it competes to similarly intervene in forex markets. In the last week alone, South Korea, Malaysia, Singapore, and Thailand are all suspected of buying Dollars to hold down their respective currencies. Meanwhile, Brazil is enhancing its capital controls and Japan stands ready to intervene should the Yen spike again.

To quote Secretary Geithner again, “This asymmetry [between nations that intervene and those that don't] in exchange rate policies creates a lot of tension. It magnifies upward pressure on those emerging-market exchange rates that are allowed to move and where capital accounts are much more open. It intensifies inflation risk in those emerging economies with undervalued exchange rates. And, finally, it generates protectionist pressures.” In short, when one country decides not to play the rules, other countries are quick to catch on. [To be fair, while the US doesn't intervene directly on behalf of the Dollar, it still deserves some blame for this tension because of QE2 and the like].

If any country appears to be taking these lessons to heart, however, it is China. To combat inflation, it has raised interest rates several times over the last twelve months, including yesterday’s surprise 25 basis point hike. Given that official inflation remains above 5% (and living here, I can tell you that the actual rate is probably 10-20%), the PBOC has no choice but to continue tightening monetary policy if it wishes to avoid social unrest. To counter the inevitable upward pressure on the Yuan, it has taken such measures as prodding Chinese firms to look abroad for acquisition targets.  China’s forex policy is designed to serve one very important end: to buttress the competitiveness of its export sector. However, there are early indications that China’s preeminent position as the world’s sweatshop may be about to slide. Anecdotal reports show that manufacturers are unnerved by wage and raw materials inflation, and are uprooting factories. In the short-term, some of this production will move inland from the coast, but even this has its limits. According to Credit Suisse, “Salaries for China’s estimated 150 million migrant workers will rise 20 to 30 percent a year for the next three to five years…’It may take a decade for China to see its export competitiveness erode, but we have seen the beginning of this happening.’ ”

China’s forex policy is designed to serve one very important end: to buttress the competitiveness of its export sector. However, there are early indications that China’s preeminent position as the world’s sweatshop may be about to slide. Anecdotal reports show that manufacturers are unnerved by wage and raw materials inflation, and are uprooting factories. In the short-term, some of this production will move inland from the coast, but even this has its limits. According to Credit Suisse, “Salaries for China’s estimated 150 million migrant workers will rise 20 to 30 percent a year for the next three to five years…’It may take a decade for China to see its export competitiveness erode, but we have seen the beginning of this happening.’ ”

With this in mind, it’s clearly futile for China to continue to focus its economic policy around low-cost, labor-intensive exports. Likewise, it’s ridiculous to continue to artificially depress the Yuan, especially if it’s serious about turning it into a global reserve currency. I think Chinese policymakers recognize this, and I stand by my earlier prediction that the Yuan will maintain a steady pace of appreciation for the foreseeable future.

No comments:

Post a Comment